Introduction

I have practiced Tai Chi for 40 years. The first 10+

years I was fortunate to have a dedicated and skilled teacher and be part of a

group of serious, but also sociable students. I also had the opportunity to

participate in workshops with Grand Master, Tung Kai Ying.

Then I moved to a place, where nobody had heard of or

cared about Tai Chi. I was reduced to practicing by myself. Slowly, Tai Chi

faded into the background and almost out of my life. But I could not let it go,

and after a couple of years, I picked it up again, gradually increasing how

much I practiced. I also re-read the classics more closely than ever, hoping to

find hints on how to improve my Tai Chi. Through a combination of reading the

classics and practicing daily, a new understanding gradually emerged.

I had long been aware that breathing corresponded to

some extent with the transfer of weight, but the underlying principles eluded

me. When I first learned Tai Chi, I was only taught the basics of how to

breathe – never when to breathe.

I was, however, introduced to the concepts of Full and

Empty in my very first Tai Chi lesson as well as their correlation with weight

distribution. But it was not until many years later, that I suddenly realized

some deeper implications of the concepts.

My Full/Empty epiphany had direct bearings on my

search for the underlying breathing pattern in the practice of Tai Chi. It

still took years of practice, and a lot of trial and error before I had the

general concepts in place. But I do now.

I have a system, and it works – at least for me.

A large part of it is firmly rooted in the classics.

Some of it, however, I never encountered anywhere, and that raises questions

such as:

·

Were my teachers unaware of these things?

·

Were they keeping secrets?

·

Am I completely wrong (it wouldn’t be the first time)?

·

Did everybody else know this, except for me?

·

Or…have I stumbled upon something important?

In the end I decided that if, indeed, I have found

something that can be useful to others, I have no right to keep it to myself.

That is the reason why I am writing this.

In the next section, Theory, I will try to explain the

principles of the system.

Theory

Full and Empty

When practicing Tai Chi, one should avoid being

double-weighted, which means that the bulk of the body should be carried by one

leg instead of being evenly distributed on both legs.

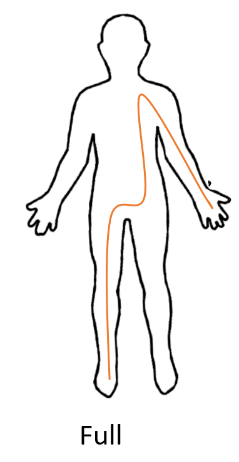

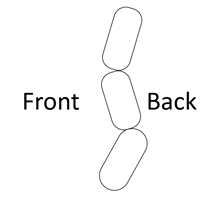

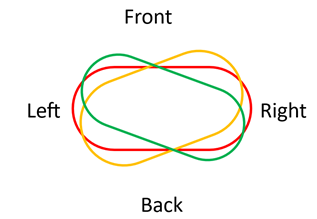

The weighted leg is Full, the other leg is Empty. When

the left leg is Full, the right hand is Full, when the right leg is Full, the

left hand is Full. This implies a connection between opposing hand and foot,

like this:

Fig. 1

Notice how the connection goes up through the left

leg, crosses through the lower dantian up through the right side of the body,

into the arm, ending in the right hand.

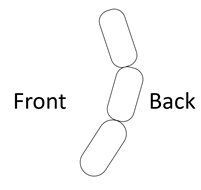

There is a corresponding path, Empty, from the

opposite foot to the opposite hand like this:

Fig. 2

When weight shifts from one foot to the other, Full

and Empty trade places.

The Empty/Full duality reflects the Yin/Yang duality

with Full as Yang and Empty as Yin. The implication is that the Full part of

the body is the source of movement, while the Empty part is being moved,

simply following along.

Once, my old teacher asked the class if we had noticed

circular or spiral sensations inside our bodies while practicing. Some had,

some had not. I had noticed something like it, but I did not know what to do

with it, and my teacher never elaborated. To me, these movements seemed to

connect with the Full/Empty paths, but I could not fit the pieces together at

the time.

More about this later, but first some thoughts on

breathing.

Breathing

When it comes to breathing, there are two points of

particular interest. The first one is how to use the nose and mouth, the second

is how to use the abdomen and lower back.

The first one has been described extensively by many

sources, so I will just sum up the basics:

Rest

the tip of the tongue on the alveolar ridge (the ridge behind the upper front

teeth).

Inhale through the nose.

Exhale through the mouth (lips

only slightly apart).

The second one needs more consideration.

All the descriptions I have seen of Taoist abdominal

breathing seem to refer to sitting meditation, and thus, in my opinion, they

are not applicable to the practice of Tai Chi. There must be a different way to

do abdominal breathing, a way that includes the limbs and is suited for a

moving body.

Trying to apply the concept of open/close to breathing

while combining it with the experience of circular movements inside the body, I

came up with this idea:

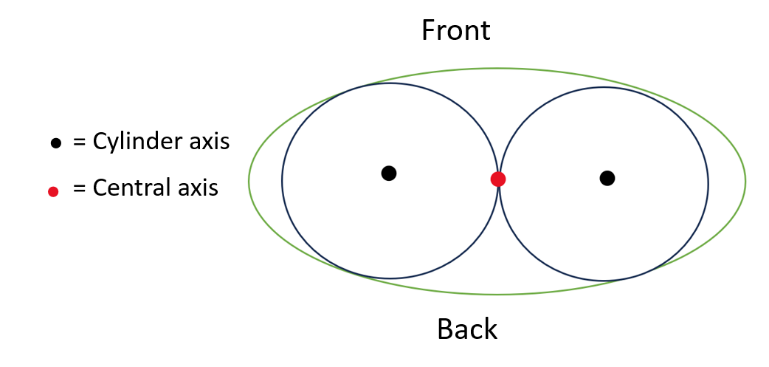

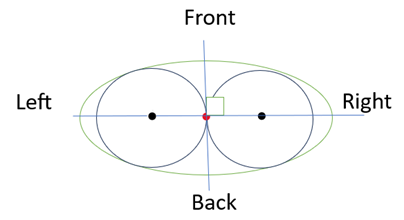

Visualize two vertical cylinders inside your abdomen –

from the diaphragm to the lower dantian. Together they fill out pretty

much the entire abdomen, touching each other precisely at the vertical Central

axis of the body. The axes of the two cylinders, respectively, correspond with

the Full/Empty paths described earlier.

Seen from above it looks a bit like this:

Fig. 3

Seen from the front it looks a bit like this:

Fig. 4

…a bit like a wringing machine.

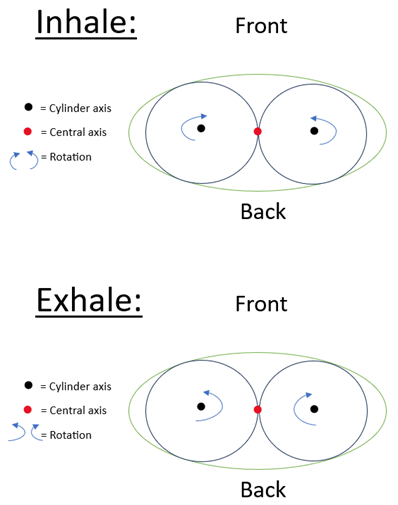

As you breathe, you visualize the cylinders rotating.

They rotate from front to back when you inhale. They rotate the opposite way

when you exhale.

Seen from above it looks like this:

Fig. 5

As you breathe, relax the shoulders, the upper torso,

and the diaphragm. Also, be aware of the Central axis of the body and keep both

that and the cylinders vertical. Relax and let the air flow freely in and out

of your lungs.

It may feel awkward at first, but it should not take

long to get the general feel of it. Still, it takes a fair amount of practice

to apply it effortlessly. If you get light-headed, sit down, breathe more

slowly, or maybe just stop trying for a while.

The three axes

Once the breathing technique is established, the next

step is to extend the centers of the breathing “cylinders” to conform with the

Full and Empty paths leading from each foot to their respective opposite hand.

These paths form two axes that are essential to every movement.

The movement is initiated by rotating the Full axis –

starting in the foot and continuing up through the leg until it passes through

the dantian, up through the opposite side of the body through the arm and into

the hand. In the dantian and in the body, the rotation sets the Empty axis in

motion, making it rotate in the opposite direction all the way from the Empty

foot to the Empty hand. The direction of the rotation corresponds with the

breathing.

All of this happens simultaneously.

The third axis is the vertical Central,axis of the

body. While the Full and Empty axes snake and bend as they rotate, the Central

axis stays straight, upright, and centered. The Central axis only turns when

the entire body turns, always keeping with the four directions - front, back,

left, and right.

It looks a bit like this:

Fig. 6a

In the torso, the Full/Empty axes align with the

Central axis to define and maintain the four main directions. Seen from above,

it looks something like this:

Fig. 6b

In theory, this system seems neat and simple, almost

easy, but putting it into practice can be quite challenging. In the next

section I will give an introduction on how to implement it.

Practice

Listening and Visualizing

Before I get into the details of how to implement the

system in practice, I need to discuss the approaches of Listening and

Visualizing, and how the two supplement each other. Every Tai Chi practitioner

uses them, even if they may call them something else. In fact this double

approach is so deeply ingrained in most people’s Tai Chi practice, that they

take it for granted without thinking about it much. This is precisely why I

think it is necessary to pause for a minute to define and discuss it.

Listening is what you do when you pay attention to the physical sensations of your

body. When you listen to – or for – something in the original sense of the

word, you need to be quiet, relaxed, and attentive in order to take in all of

the different sounds you hear. The longer you can stay in this unfocused but

attentive mindset, the more sounds you will eventually be able to distinguish.

The approach is the same when you Listen to your body:

Relax and try to neither focus on, nor block out any physical sensation. That

way you will gradually increase your body awareness.

Visualizing is what you do when you imagine various structures,

places, or processes in your body. When you visualize something in the original

sense of the word, you try to see something that is not there, building a

mental image of it. It is a focused act of creation – precisely the opposite of

listening.

This is the approach you use in Tai Chi practice when,

for example, you imagine that you are suspended from the top of your head, or

when you focus on your dantian.

You need to do Listening and Visualizing

simultaneously. And you need to balance the two, so they can benefit from each

other.

When you Visualize too hard or too much, you will

misinterpret or unconsciously ignore a lot of the sensory input you get from

your body. You might even imagine or Visualize some things so strongly, that

you deceive yourself into believing that they are fixed and real. But whatever

mental images you may have of the underlying principles and structures of the

movements, they should constantly be tested and challenged by what your body

tells you, and where it tells you it wants to go.

If, on the other hand, you do not Visualize enough,

the sheer amount of your body sensations will soon swamp you and lead you in

conflicting directions. You need to have some underlying idea or image of what

you are doing in order to structure and make sense of what your body is telling

you.

You can really not Listen too much to your body. But

it is important that you keep an open mind, so you do not hear only what you

expect to hear, instead of what your body is actually telling you. It is

equally important to remember that you should not let yourself be distracted by

the various sensations coming from different parts of your body. Keep your

focus on the basics and trust your body to take care of the details by itself.

Be aware, but do not interfere.

Everybody will find themselves making the errors, I

have just described. And not just once – we make them continually, over and

over, often in new and unexpected ways. This is not a bad thing. Every time we

find ourselves making an error, it means that we have gained a slightly deeper

understanding.

And now, back to the main subject.

To get a fuller understanding of the following

paragraphs, it may be helpful to pause from reading at regular intervals and

get on your feet to try and apply the content in practice. If you choose to

apply it to actual Tai Chi movements, I suggest you start with Brush Knee,

Repulse Monkey, or Parting Horse’s Mane, since these are done both to the left

and the right side.

Tracing the paths

The Full and Empty axes can be Visualized in many

different ways. For example, as garden hose, string or twine, gear cables,

steel wire, or simply just narrow canals or vessels – either empty, or filled

with air or fluid. Anything long, thin, and flexible will do for a start – your

perception and Visualization of them will develop and change over time anyway.

You Visualize the axis as starting in the center of

the foot sole, going through the center of the ankle, the central axis of the

lower leg, the center of the knee, and the central axis of the thigh. At the

top of the thigh, it turns sideways at an approximately 75° angle, going in a fairly straight diagonal line

through the dantian and continuing until it turns upwards again at the top of

the pelvic bone to go vertically through the center of the opposite side of the

torso in a straight line parallel to the body’s central axis. At shoulder level

it turns again to go through the shoulder, the central axis of the upper arm,

the elbow, the central axis of the lower arm, the wrist, and ending in the palm

of the hand.

This is not easy, but try it anyway. Start with just

the weighted foot – the Full axis – and proceed like this:

Stand relaxed with parallel feet. Transfer your body

weight to one foot and open that foot to a 45° angle. Visualize the rotation of

the Full axis – outwards in the foot and leg, inwards in the opposite side of

the torso – while you inhale. Only rotate the axis, the surrounding muscles

simply stay relaxed. They may move slightly, but that is not your concern. At

the same time, put the other foot forward as far as you can without shifting

the weight.

When you are no longer inhaling, you let the weight

shift on to the front foot, exhaling at the same time. As soon as the weight

begins to shift and you start to exhale, the front foot becomes the Full foot,

rotating the new Full axis inwards in the foot and leg, and outwards in the

opposite side of the torso.

When almost all weight is transferred, you open the

Full foot 45°, lift the back leg and let it come forwards, inhaling at the same

time. As you inhale, the rotation in the Full leg reverses to go outwards in

the foot and leg, and inwards in the opposite side of the body.

Repeat the procedure for each step you take.

Relax as much as possible and pay attention to the

Central body axis to maintain balance and direction. Both the lower and the

upper parts of the torso as well as the thighs (to the extent that it is

possible) should face forward at all times. The direction must be clear and

well-defined.

Setting the Empty axis in motion

Even if you are only actively moving the Full axis,

you still need to Visualize how the Empty axis is being moved as well. There is

more than one way to do this.

One way to do it, is to use the image of the cylinders

I presented in the section on breathing (fig. 3-5). The active cylinder touches

the passive cylinder, which will be set in motion when the active cylinder

begins to rotate, thus moving the entire Empty axis from foot to hand.

Again, it is important to stress that this is just a

mental image to help you focus and structure the movement, not a physical

reality. You need to relax your actual body as much as possible, and Listen to

it while you Visualize.

Another way to do it, is to focus on the dantian,

where the Full and Empty axes pass through each other. If you Visualize the

axes going through the dantian at an angle less than 45° on the vertical plane,

it is possible to imagine how the Full axis creates a “backwards” rotation when

you inhale and a “forwards” rotation when you exhale. Where the axes merge in

the dantian, the rotation of the Full axis will set the Empty axis in motion.

It looks a bit like this:

Fig. 7

Often, “turning the waist” is interpreted as turning

or rotating the upper body from side to side, while the foundation – hips and

legs – keep the direction. This is a different kind of “turning the waist”, but

in my experience it is a better one. It eliminates unnecessary twisting of the

body, gives clearer focus and direction to the movement, and keeps the upper

and lower parts of the body connected.

This second method is more challenging than the first,

but at the same time also more rewarding. If you are really ambitious, you can

try to do both simultaneously.

Advice

Practicing Tai Chi is an individual experience. We all

have different backgrounds, different mentalities, different physical

challenges and advantages. There is no one-size-fits-all. Still, I will throw

in a bit of general advice at this point.

Firstly, if you choose to implement the three axes by

first focusing on the Central axis, then incorporating the Full axis, and

finally getting to the Empty axis (which seems to me like a sensible way to do

it), you can easily get the feeling that the Empty axis needs extra attention,

once you finally get to it. But if you pay too much attention to the Empty

axis, you may find yourself moving it, rotating it, to help it along. Suddenly

you are treating the Empty axis as if it were Full. This is a mistake. The best

you can do for the Empty axis is to clear whatever mental and physical

obstacles it may encounter by relaxing your body and keeping an open mind.

Again, be aware, but do not interfere.

Secondly, if you concentrate too hard on the Full

axis, your Visualization of it may drift towards the center of the body, mixing

it up with the Central axis. Try to pay equal attention to all three axes at

all times, keeping them separated, and remember that everything needs to be

balanced around the center.

Thirdly, once you begin to get a sense of the Full and

Empty axes, you might experience that they are seemingly not where they are

supposed to be. They may feel more or less displaced, maybe even bending and

going off into unexpected directions. You should neither ignore this, nor

should you try to force the axes to go where you think they ought to be. It is

your body telling you that you need to make adjustments and trying to show you

how. You must relax, Listen, and try to reach a compromise between what you

want, and what your body tells you. This way you will progress more quickly

than if you try to force things. It takes more than one attempt, maybe even

more than a thousand attempts. Even so, it is still the most efficient way.

Many of the adjustments you need to make have to do

with alignment.

Alignment

Keeping the body aligned is essential to Tai Chi

practice. It is a huge and complex topic that I can never hope to cover in

full. There are many moving parts, which all need to align. When you correct

one small bit of your alignment, you need to realign the rest of the body as

well. Furthermore, as soon as you start moving, your alignment will begin to

fluctuate and change, so you constantly need to adjust it. It is an endless

process.

Therefore, I will only put down some general

observations on alignment of the torso.

I choose to divide the torso into three parts:

·

The upper part, which is from the shoulders to the diaphragm – essentially

the rib cage.

·

The middle part, which is between the diaphragm and the pelvic bone –

essentially the gut.

·

The lower part, which is essentially the pelvic area – including the top of

the thighs. The lower dantian is located in the middle of the lower part.

These three need to align in three dimensions:

Vertical, sideways, and directional.

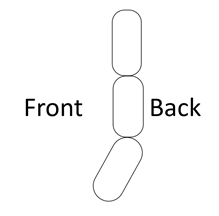

Vertical alignment means that the upper and middle parts of the torso are vertical,

and positioned on top of the lower part. Seen from the side, it looks a bit

like this:

Fig. 8

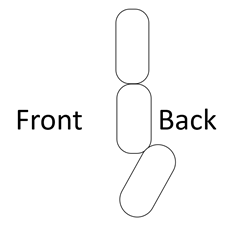

The upper and middle parts should not slide

downwards and forwards so that the buttocks stick out, like this (still seen

from the side):

Fig 9

Neither should they tilt,

so that the back sways, or the shoulders hunch like these (still seen from the

side):

Fig 10a Fig 10b

Fig 10b

Sideways alignment means that the three parts of the torso should be…aligned

sideways – a bit like this (seen from the front):

Fig 11

They should not protrude sideways like this:

Fig. 12a  Fig. 12b

Fig. 12b  Fig. 12c

Fig. 12c

Nor should they tilt like this:

Fig. 13a  Fig. 13b

Fig. 13b

Directional alignment means that all three parts of the torso

should be facing in the same direction. It looks a bit like this (seen from

above):

Fig. 14

Directional alignment is easily upset. Every time the

body turns or the weight shifts, the three parts of the torso tend to lose

directional alignment, like this for example:

Fig. 15a

…or this:

Fig 15b

The important thing to remember here is to turn

the body, not twist it.

-o0o-

The figures above are somewhat exaggerated to

illustrate their points clearly, but even slight imbalances can have

significant impact. More often than not, these imbalances will occur as

combinations of the various types of misalignment.

Once you become aware of an imbalance, the best way to

try and correct it is to use a combination of gravity and focused relaxing.

Release the tension that causes the imbalance and let gravity draw the body

towards a balanced state. Do not use force to help it along.

Be aware that the three parts of the torso do not have

fixed shapes and sizes. They are all three soft and pliable to a certain

extent, each in their way. The more you relax and Listen to your body, the more

you will appreciate this.

Breathing - again

So far, I have covered the breathing technique and how

it is related to the three axes in both theory and practice. But one important

thing is still missing: When to inhale and when to exhale? I have

touched on it briefly already, and I will discuss it a bit more below, but some

of it you will simply have to figure out for yourself. It depends on many

things, for example which Tai Chi style you practice, how fast/slow you

practice, and your level of skill.

The core of my daily practice is the Yang style slow

set as taught by Grand Master Tung Kai Ying. When I do this set, I exhale every

time I shift the weight. At first, I thought there were a few exceptions to

this rule, but over the years I eliminated those. This does not mean, however,

that I only exhale when I shift the weight. For example, from the posture White

Crane Spreading Wings I inhale when the right hand comes down in front of the

body, exhale as the left hand moves in front of the body and the right hand

goes backwards, inhale as the left hand parries to the left, the left leg steps

out, and the right hand comes forwards and passes the ear. I finally exhale

again as I shift the weight forwards, pushing with the right hand and brushing

with the left, coming into the posture Brush Knee. So there’s an extra breath

right there.

I practice other sets as well, which have distinctly

different breathing patterns. And then there are sets I don’t know at all –

they may also be quite different.

As a general rule, one might say that offensive moves

such as punching and pushing are associated with exhaling, while defensive

moves such as parrying and yielding are associated with inhaling.

If you practice a set fairly quickly, you may find

yourself taking fewer breaths than if you practice the same set more slowly.

If you have a certain level of skill, your breathing

may be so deep that you can skip a breath in some places, if that works better

for you.

In the end, though, I think the ideal breathing

pattern is closely connected to how the movements are joined together in the

actual set you practice. I think that if you experiment, you will find that

while most parts of the breathing pattern come naturally, a few can be tricky

to figure out.

Conclusion

The ideas I have presented here have matured and

developed over more than a decade. They have undergone many changes and

adjustments, as I have tried to implement them in my daily practice. They are

still not fully developed and probably never will be. Writing this essay, for

example, caused me to focus on aspects I had neglected, and helped me make a

number of adjustments.

By now, though, I am convinced that the basic

principles of this system are sound, and that if they are followed, they can

improve most people’s Tai Chi. But even if the principles are relatively few

and simple, they can still be difficult to follow. There is a lot to keep track

of. Every time you think that you have got it right, you will invariably

realize at some point that you are not doing what you think you are doing.

Every day, when I practice Tai Chi, I try to implement

these ideas to perfection. I never come close to actually doing so. But I often

fail in new and interesting ways, learning or realizing things I did not know

before – I grow. One might say that I fail successfully. Even writing this

essay has inspired me and helped me correct mistakes I was making. I hope

reading it can be helpful and inspiring to others, so that they too may fail

successfully.

Peter Skov Larsen

Except for the body outline used to make figs 1, 2, 6a, and 16 (appendix B)

which is from Wikimedia commons, all text and illustrations are created by me.

This material may be copied and distributed in part or in full, as long as it

is not for profit, and the original source is cited.

Questions and comments can be directed to peter@friktion.com

Appendix A

Two Ways of Relaxing

Introduction

If I could give only one piece of advice on how to best practice Tai Chi,

it would be this: Relax. You must consciously and intentionally relax your body

while practicing Tai Chi. If you do not relax, your understanding of Tai Chi

will never be more than superficial at best.

Broadly speaking, relaxing means the release or relief of muscular tension.

At any time, all the muscles of the body are in various states of tension that

can go from very little to very much – from completely slack to rock hard. As

the tension of individual muscles increases or decreases, the overall pattern

of muscle tension changes. This is how the body moves.

It is the fluctuations in an individual’s muscle tension patterns that

makes their bodies move. But people’s overall tension levels can differ widely.

There may be more or less the same scope of variation in individual muscle

tension patterns, but some people have higher tension baselines than others.

That which feels relaxed to one person may feel moderately tense to another,

and that which feels a bit tense to one person may feel almost relaxed to

another.

I am convinced that, on the whole, having a low muscle-tension baseline is

better than having a high muscle-tension baseline. I think this goal can be

achieved by actively practicing the relaxation of overall muscle-tension over a

sustained period of time. In the following, I will present two mental exercises

which, when used in combination, can be used to actively practice sustained

relaxing. They were originally meant to be used in Tai Chi practice, but it

should be fairly simple to apply them to other scenarios.

Both methods involve a fair amount of visualizing. This comes easy to some,

while others find it more difficult. But no matter how bad you may be at it at

first, it will still have an effect, and you will improve with practice.

Exercise 1: Hanging

Most Tai Chi practitioners have at some point been asked to imagine their

heads being suspended, hanging from a string at the top of the head or

something similar. This method uses the same principle, but instead of just the

head, you imagine your entire body as a marionette doll, suspended from above,

loosely stringed together in all major joints. The doll’s feet are just barely

touching the ground.

Stand up. Visualize from the top of the head and downwards– the head

hanging from a string at the top, the body hanging from the neck, the arms

hanging from the shoulders, the thighs hanging from the hips, the lower legs

hanging from the knees, and the feet hanging from the ankles, just barely

touching the ground.

Relax and allow gravity to gently release all tension in the joints or in

the limbs.

Exercise 2: Stacking

This exercise seems to be exactly the opposite of the first one, but it

will still relax you, just in a different way. This time, you imagine your body

as a set of building blocks or Jenga blocks, that you stack to build a tower.

It may be useful to imagine the blocks as not weighing very much.

You are still standing. This time you visualize from the floor and upwards.

The feet resting on the floor, the lower legs resting on the feet, the thighs

resting on the lower legs, the body resting on the thighs, the neck and

shoulders resting on the body, and the head resting on the neck.

Gravity keeps every part of your body in place, so you can safely relax and

let go of all tension.

Combining Hanging and Stacking

Both exercises are useful, each in their way. But it is when you combine

the two that things really start happening. You do it like this:

First, do the Hanging exercise very slowly and thoroughly. Pay careful

attention to the physical sensations of your body.

Next, do the Stacking exercise in the same way. Slowly and thoroughly,

still paying attention to the physical sensations of your body.

Now shift between the two, increasing the speed a bit, making the intervals

between the shifts shorter. But do not go too fast – it is about relaxing,

after all.

When you feel comfortable shifting between Hanging and Stacking, it is time

to coordinate them with your breathing. It is quite simple: Every time you

inhale, you do Hanging, every time you exhale, you do Stacking. Once you get

the hang of that, you should always let the rhythm of your breathing decide the

exercise, not the other way around.

Conclusion

This double exercise relies on gravity and is meant to be done while

standing, walking, or maybe even running. You can do it at any time or place -

walking down the street, for example, or waiting in line at the supermarket.

If, however, you pay enough attention to the different physical sensations of

Hanging and Stacking respectively, you will eventually be able to reproduce

them while sitting or lying down. Then you can also do the exercise while

watching a movie, or lying in your bed.

But it is very important to be aware that doing this exercise can very

easily induce a state of meditation or absent-mindedness. Doing it in a sitting

or lying position may even cause you to nod off.

This is why it is somewhat unwise to do it while you have to pay attention

to other things - during social interactions, for example, or while driving.

Even if it is a nice little exercise that can be done almost anywhere at

any time, there is still a time and a place for everything.

Appendix B

Threading the nine-bend pearl

In the Tai Chi classic on how to understand and

practice the thirteen postures, you will find this line: ”Directing the

qi is like threading a pearl with nine bends in the hole. There is nowhere it

does not penetrate.” (translation: Wile). This sounds nice and

poetic, but what does it actually mean? Actually, I have a few thoughts on how

this could apply to the Three Axes system of understanding Tai Chi.

Firstly, it refers to directing the qi with the mind,

threading it through the pearl (which I take to be the body). If you consider

the way you thread an actual pearl, you will find that you twist the thread,

rolling it between your fingertips to help it move forwards, going through the

hole of the pearl. This brings to mind a Visualization of the Full axis as it

curves through the body from foot to opposite hand. The turning of the Full

axis along its path is just like the twisting of the thread through the pearl.

What then, are the nine bends? Should the number even

be taken literally in this context, or does it hold a symbolic or metaphorical

meaning?

When I was young, I dabbled in Yi Jing divination, and

ever since then I have associated the number nine with old Yang - the state of

Yang just before it turns into Yin.

Also back in the day, my teacher would often repeat

exercises nine times, so I started doing so too. Today it has become a habit.

There is no rational reason for it, but it works well.

There are other symbolic and metaphorical uses of the

number nine in Taoist philosophy, but I fear that exploring that path will only

lead to confusion.

So instead, I choose to take the number at face value.

Assuming that the pearl is the body, and the hole is

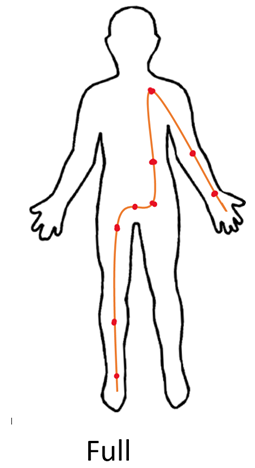

the path of the Full axis, where are the bends then?

The joints seem to be the obvious place to start. That

would be the ankle, the knee, the shoulder, the elbow and the wrist. But that

only makes five, so another four are needed.

Since the Full axis makes a sharp turn inwards where

the thigh attaches to the bottom of the pelvic bone, and another sharp turn

upwards at the top of the pelvic bone on the opposite side of the body, those

two points are obvious candidates, raising the total to seven.

The lower dantian can not be left out. That

makes eight.

I think the ninth and final bend is found at the point

where the Full axis crosses from the middle torso into the upper torso. It may

not be a bend as such, as long as the middle and upper torsos are directionally

aligned. But, most of the time, they are not. That is what makes this point so

difficult to “thread”. It also makes it a key to aligning the torso

directionally. Thus, I think it qualifies.

In a drawing, the positions of the bends look a bit

like this:

Fig.

16

I am aware that this interpretation of the nine-bend

pearl is somewhat speculative, and that a number of objections could be raised

against it. I have seen other, well-argued, explanations of the nine-bend

pearl, which came to quite different conclusions. I think that, ultimately, we

will never fully know the meaning and intention of the original text.

But I also think that this interpretation can function

as a useful mental check-list in the everyday practice of Tai Chi.